Challenging student behavior can be one of the most exhausting and stressful parts of teaching. Especially when it just keeps happening. Unfortunately most of us didn’t receive much training on what to do in our teacher prep programs.

We need classroom and behavior management strategies we can put in place tomorrow. Things that are practical. Straightforward. Simple. And especially effective.

Behavior Contracts are a strong fit for that need. They’re a low-effort, proactive, positive intervention that’s pretty much as simple as laying out a clear-cut agreement with students up front and then following through on it.

What is a behavior contract?

At its simplest, a behavior contract is a written agreement between a student and teacher to work toward a common goal of student success. The teacher spells out specific expectations for the student’s behavior, focusing on positive behavior that the teacher wants to see more.

And no contract is complete without terms that benefit both parties, so the agreement also includes some sort of reward the student will earn for improved behavior. It’s a collaborative process and meant to be mutually beneficial.

Among behavioral folks and in research articles, you might hear these called contingency contracts. Rest assured, contingency contracting is the same thing.

What behavior problems can behavior contracts help with?

A great thing about behavior contracts is they can be used to address virtually any problem behavior that shows up in your school. As long as your student has the skills to communicate with you and understand the contract itself, the sky’s pretty much the limit.

For example, behavior contracts have been used to improve things like students talking out, leaving their seat, being off-task, disrupting the class, and so on. They can also help increase the positive behaviors you want to see more of like class participation and appropriate interactions with peers.

Are behavior contracts an evidence-based practice?

The researchers synthesized results from 18 studies of behavior contracts for 58 children. They found an overall positive impact (specifically, a moderately strong effect size) on a variety of targeted outcomes, such as reducing problem behaviors (e.g., destructiveness, disengagement) and improving desired behaviors (e.g., engagement, appropriate social interactions, task completion, correct academic responses).

How to implement behavior contracts

Behavior contracts include three main components: behavior, reward, and recording method. Contracts can be implemented in a few simple steps:

- Identify the target behavior you want to change. Focus on a specific observable behavior that’s a high priority for you to improve. You can focus on other behaviors later in the process after you’ve experienced success around your biggest priority.

- Hold a meeting with the student (and any others involved). It’s very important for the student to participate and to have a voice in the development of the contract. This is an opportunity to lay out very clear expectations for the student, to problem-solve collaboratively, and to build positive rapport between student and teacher.

- Work together with the student to define the behavior you want to see. Focus most on the appropriate behavior you want the student to develop.

- Work together with the student to identify appropriate rewards for meeting behavior expectations (and additional consequences, if needed). Be sure to pick something of value to the student that will motivate them toward behavior change. Determine how often the student can earn the rewards (i.e., how much appropriate behavior is required before the student can earn the reward?)

- Make a plan for monitoring and evaluation. Data plays a crucial role in understanding objectively whether an intervention is working or not. Consider how you will record data about the student’s behavior and how often you will analyze the data to guide your efforts.

- Sign the contract with the student.

- Remind the student of the contract regularly, and provide the reward as soon as possible once it’s been earned. A key goal here should be for the student to be successful with behavior and earn the reward in the contract. Consider how you can set the student up to be more likely to succeed with the contract.

Behavior Contract Templates and Examples

In my post on behavior contract templates, I provide 28 ready-to-go options for different student groups and needs along with multiple sample behavior contracts addressing different student behaviors. The templates include interactive, fillable PDFs and editable Google & Word documents that all include key components for successful contracts. 12 of the templates are my own and include features like clickable checklists of common behaviors, connections to PBIS schoolwide expectations, and school-home collaboration components.

Get Limened’s 12 Fillable PDF Templates

by signing up for our newsletter

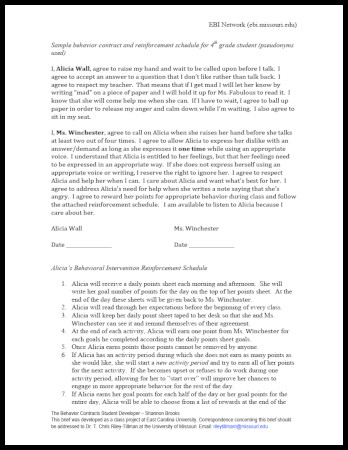

Here are a few template and example resources from other sites:

Video Examples of Behavior Contracts

Kansas TASN Secondary Behavior Contract Example

(if video won’t play, see it here)

Behavior Contract Tips

- It’s critical for students to be active participants in developing a behavior contract—that’s part of the secret sauce!

- Make sure the reward is something that motivates the student. To support students to identify something motivating, you might help them think about what they like to do in their free time or conduct a reinforcer survey or preference assessment.

- Student preferences and motivators may change over time, so it may be helpful to check in with the student and change the reward every once in a while.

- Make educated decisions about how the intervention is going by collecting and analyzing data—both baseline and progress monitoring data to make sure you’re having the desired impact on the student.

- If it’s not working, there are two areas you might start with for problem-solving. 1) Is the criterion to earn the reward too difficult for the student? 2) Is a different reward needed to increase the student’s motivation? Of course, you might benefit from just asking the student first why things aren’t working out.