Choice making is one of my favorite practical behavior intervention strategies. It’s so simple, yet remarkably powerful.

Perhaps it’s related to what many teachers cite as the reason for student misbehavior—control. Although control may not be a useful function for developing interventions, it’s a concept I run across often when supporting educators.

“He does it for control.” “She just wants to control things.”

There are a lot of things in a typical school day over which a student doesn’t have control. The schedule is laid out. Activities and tasks are prescribed. Bathroom breaks are squeezed into short time periods or require special permission. And so on.

Maybe simply providing options for inconsequential matters gives students enough control that they don’t need misbehavior. They can choose what they’d most prefer or at least what they find least aversive. And maybe that’s enough to make the school day tolerable.

I know I like to have choices.

I think giving students choices is a kind way to treat them with dignity and personhood while promoting their own self-determination and self-advocacy skills. Choice making can help a student develop as a person while also improving their behavior.

In this guide, I walk you through all the ins and outs of choice making as a strategy in the classroom and beyond to promote positive student behavior.

What is Choice Making?

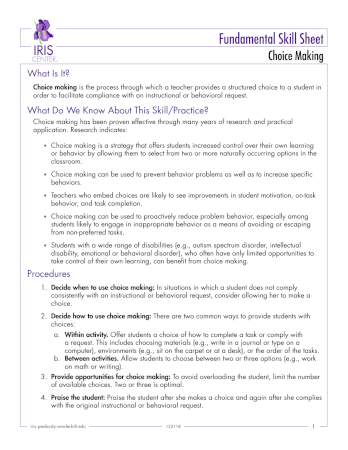

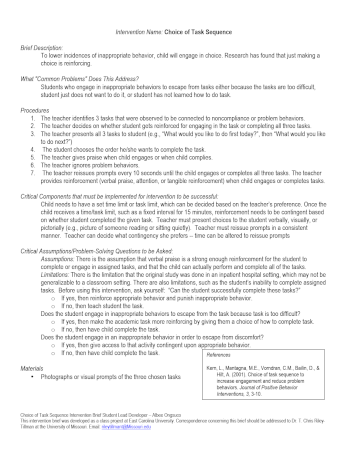

Choice making is simply giving a student two or more options prior to a situation or task where some form of problem behavior is predictable.

Choices can be across tasks or activities (such as what order to work on assignments), within tasks or activities (such as what materials to use like pen & paper or a computer), or other environmental factors (such as where to sit when completing a task).

The teacher makes prearrangements for the choice (preparing any needed materials or adaptations), tells the student the options, and honors and reinforces whatever choice the student makes.

It’s important to note that choice making is not about making veiled threats of punishment if the student doesn’t comply (e.g., “You have a choice here: you can either start working on your math, or you can go to the office to see the principal. It’s your choice.”). Rather, choice making is a more positive approach that presumes compliance and gives the student options for how to comply or engage. For example, “It’s time for math work. Do you want to work on your own at your desk or come back to our round table to work with a partner?”

Student choices might include:

- Order of assignments/tasks/content areas

- An activity menu (e.g., pick any 3 activities on a list of options)

- Which items to Complete Within a Task/Activity (e.g., odds or evens)

- Product Format (e.g., speech or video)

- Where to work

- With whom to work

- Materials to use

- Reinforcer/reward to work for

- Other environmental factors

What Behavior Problems Can Choice Help with?

Choice can improve a variety of behaviors. It’s especially helpful for improving compliance by increasing the probability students will follow directions. Choice can also increase a student’s motivation and level of engagement on tasks as well as assignment completion.

Researchers have also demonstrated that choice making can reduce various disruptive and destructive behaviors. This is especially true when a student engages in these challenging behaviors to escape or avoid certain tasks or other factors (like certain people or settings).

Moreover, choice can improve various academic outcomes, such as accuracy and fluency. Essentially, as students become more likely to follow directions and become focused, engaged, and on-task, they learn more, complete more, and misbehave less.

Furthermore, as students practice expressing their own preferences, their self-determination can grow as well. That’s a critical life-long skill that can improve their quality of life and long-term outcomes.

Is Choice an Evidence-Based Practice?

In brief, choice making is a promising practice with fairly substantial positive evidence in support of its benefits. However, there’s not quite enough evidence of sufficient methodological rigor yet to fully classify it as an evidence-based practice.

In the first article, a team of researchers systematically reviewed the quality and findings of studies of instructional choice making in schools to determine whether choice could be classified as an evidence-based practice. They reviewed 26 studies of choice, which included 73 students. The studies had a wide range of small to moderate positive effects on a wide variety of student behaviors, such as improving engagement level, increasing amount and speed of task completion, improving accuracy on tasks, increasing oral reading fluency, reducing disruption, and decreasing destructive behaviors. However, many studies did not meet sufficient criteria (e.g., too few participants) to count toward classifying choice as evidence-based, so the researchers classified it as currently having insufficient evidence.

In the second article, the researchers synthesized results in a “mega review” of 50 different meta-analyses and systematic reviews for 20 interventions for students with challenging behavior. Though insufficient evidence exists so far, due to a range of positive effects in the existing research, choice was identified as a promising practice.

How to Implement Choice Making

Choice is a very simple strategy to implement that you can keep in your back pocket to use on the fly. However, it can be helpful to think it through carefully and implement it systematically. Especially when you really want to promote student behavior change for a specific student or group of students. Choice can be implemented in a few steps:

- Prioritize the problem behavior you most want to change. Consider what observable problem behavior is a high priority for intervention. Focus on that behavior for this intervention. You can address other behaviors once you’ve experienced some success with your biggest priority.

- Plan appropriate choices that you find acceptable. Identify two or more options you can live with that are appropriate for the instructional activity or context in which the student’s problem behavior occurs. It may be helpful to come up with a broad menu of options you might be able to use for different scenarios. These can be across-activity choices (e.g., which task do you want to do first? Pick 3 activities from this menu.) or within-activity choices (e.g., do you want to work on your own or with someone else? What do you want to use to complete this assignment–pen & paper or the computer?).

- Prepare any materials, modifications, or other arrangements needed to implement the planned choice. Consider whether your choice options require any advanced preparation, and make sure to set those things up. This could be things like preparing special versions of worksheets, making sure special seating is available, checking in with a colleague to be sure they can offer support, or setting up needed supplies or technology. For example, if your choice involves the option to use an iPad for the writing task, make sure that thing is charged up! The last thing you probably want is to tell a kid with challenging behavior the iPad he just chose is dead.

- Provide choice prior to situations when the problem behavior is predictable. Be sure to pick something of value to the student that will motivate them toward behavior change. Determine how often the student can earn the rewards (i.e., how much appropriate behavior is required before the student can earn the reward?)

- Give wait-time to allow the student to make the choice. Give the student some time to consider the options and make their choice. If the student doesn’t make a choice after some wait time, prompt them to pick an option.

- Allow the student to engage in the option they chose, and reinforce choice making. Provide whichever option the student chooses. Make this a positive interaction by reinforcing choice making, which you can do by providing the option and behavior-specific praise (e.g., “Great job choosing to use the iPad for your writing.”)

- Monitor the impact of choice on the student’s behavior using data. Consider what form of data you will need to monitor the student’s behavior over time as you implement choice as well as how you’ll use it to make data. Simple options exist, such as using the Direct Behavior Rating to monitor engagement, respect, following directions, disruptions, or any other behavior you want to track.

Choice Making Guides, Examples, & Resources

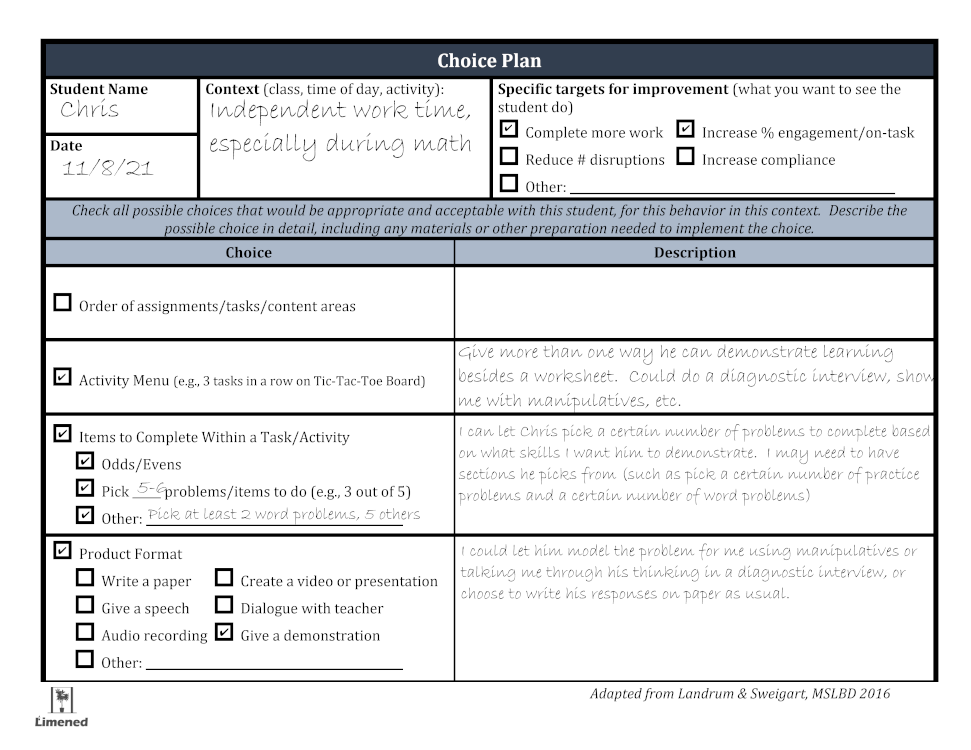

In this article, I walk through some personal stories and examples of ways to provide choices to students using a downloadable choice making planning template to guide your intervention efforts. The template is a fillable PDF with checklists of a wide variety of choice options. Several of my examples of student choice in action highlight how teachers might plan for multiple scenarios.

Video Examples of Choice Making

Kansas TASN Choice Making Example

Choice Making Tips

- Be sure to honor whatever choice the student makes. Be positive about the choice rather than engaging in any form of negativity (e.g., “Really? You’re gonna choose the computer…again?!”). This is a great chance for specific positive feedback (“Great choice to use the computer for your assignment; let’s get you set up!”).

- For some students, you may need to explicitly teach them how to engage in choice making. This might mean modeling, guided practice, and independent practice as well as prompting to help them engage successfully in making choices.

- Make sure the choices you provide are appropriate for the student (e.g., age, developmental level, culture, preferences).

- Choice is unlikely to work well for increasing engagement in a task or compliance with directions if the student doesn’t have the required skills to follow through. So make sure students are able to engage in whatever skills they need, and provide instruction or additional supports if needed.

- Some students may respond better if choices are provided in other formats than verbal. For example, providing a choice board with pictures of options may be a helpful visual support for choice making. (Here are some examples of related visual supports.)

- You can provide choices class-wide as well as to specific individuals.

- Come up with a wide selection of choices you can use for the context in which you want to improve student behavior, so you can vary the options you provide over time.