In basketball, basic skills like lay ups, passing, free throws, and ball handling may seem to be just that—basic. However, these skills are the foundations for success in a game and set players up for more advanced plays. It’s no wonder a great deal of practice is dedicated to their development.

It’s the same in the classroom. Fundamental classroom management strategies set students up to be successful learners who are actively engaged in instruction (and not misbehavior!). These fundamentals serve as a foundation for more advanced behavior intervention as well.

Although these strategies may be simple and intuitive (and therefore seem less worthy of attention), without effective classroom management, many in our profession are drowning in behavior problems and looking for a way out.

Consider, for example, the behavior in this teacher’s class where he’s really struggling with a student named Dan (you’ll know him when you see him!). If he were a colleague looking for your help reigning Dan in, consider what you might recommend (Note: it’s a Karate/History class, and I have no idea why! But a great display for us to learn from):

Would you jump right to an intensive intervention plan for Dan? Or suggest praying desperately for him to get some ADHD meds?

Probably not, based on my experience discussing this scenario with hundreds of teachers in professional learning sessions.

No, most teachers don’t talk much about Dan at all. The focus instead is usually on the teacher’s general classroom management and instruction. Teachers share ideas like:

- The instructional format (and content) seems unengaging, with one student answering one question. Rinse and repeat. There’s no role for any other student in this setup, and students like Dan, especially, know they won’t have to participate.

- The physical structure (including where the teacher is) is not conducive to promoting engaged learning behavior. Teachers have shared ideas like changing the chair layout (e.g. a circle, small groups for partner discussions) or how they would either move Dan up front nearby or move around themselves to be near Dan, using the power of proximity to improve his behavior.

- The teacher only attends to inappropriate behavior, largely ignoring all the appropriate behavior going on throughout the lesson while paying strong attention through harsh reprimands to inappropriate behavior.

- The teacher does not go over any expectations for the lesson, seeming to count on students to just know how to engage. And many of them do, but not Dan! On that note, though, many teachers note the missed opportunity when Dan does raise his hand for once and doesn’t get called on.

All of these observations about teacher practices in Dan’s class are related to essential classroom management strategies. In this guide, I walk you through all the ins and outs of 5 core classroom practices that set students up for behavioral success.

What is Classroom Management?

Classroom management is the set of strategies and techniques teachers use to foster and maintain positive and productive learning environments, by promoting appropriate student behavior and minimizing disruptions.

Although I sometimes encounter educators whose first line of thinking about classroom management is trying to come up with a solid menu of punishments for different behaviors, effective strategies are more proactive and positive in nature. And they require a little bit of careful planning.

Ideally, classroom management is planned and introduced intentionally to students at the start of the school year. Teachers might think through their behavioral expectations of students and how to promote those behaviors through structure, instruction, and planned responses.

What are Effective Classroom Management Strategies?

Five primary classroom management practices have been identified that work together to promote better student behavior. (And there are many options for other classroom management strategies that fit within these five). The five practices include

- Maximize structure and predictability

- Post, teach, review, monitor, and reinforce expectations

- Actively engage students in instruction

- Implement a continuum of responses to acknowledge appropriate behavior

- Implement a continuum of responses to inappropriate behavior

1. Maximize structure and predictability

This classroom management strategy involves two main elements to build structure, including (a) setting up the classroom layout, and (b) establishing classroom routines.

When designing the layout of your classroom, it’s helpful to consider what will increase the likelihood that students are engaged in learning and prevent or limit disruptive behaviors. This might begin with considering what kinds of actively engaging learning strategies you plan to employ and what desk/furniture arrangements lend themselves to student success (e.g., table groups vs. rows for more partner & small group activities).

It’s also important to think about movement in the classroom, both for yourself and your students. Active supervision (including moving around the classroom, engaging with students, and giving them feedback frequently, especially specific positive feedback) is a powerful predictor of better student behavior. Active supervision requires free, easy movement around the classroom, so make sure you consider spacing between desks to give yourself room to get around (as much as possible–I know some of you are out there with 40 students in a broom closet, so extra space is a challenge!).

Providing room for traffic flow also prevents congestion of students. And clusters of students, especially during transitions and down-times, can be a predictor of problematic behavior. Give students space to move if you can, and consider spacing in areas they may be likely to gather (e.g., pencil sharpener, homework cubby).

Establishing and teaching classroom routines is a critical part of classroom structure to help students fluidly meet expectations during common, daily activities. When routines are well-established, students know just what to do and when. And common challenges like transitions end up much smoother, with far fewer disruptions and increased time for instruction.

Consider for example the transition routine in this clip:

Although some find this degree of structure to be a bit too intense (or even militaristic!), take a moment to consider what we see happening. Students know exactly what to do (e.g., stand up, push in chairs) and where to go (i.e., a specific carpet square). And what happens?? Consider: when does instruction begin? Before they even make it to the carpet! Students are choral responding before the transition is even complete. Transitions between instructional activities are where we often lose a lot of time and experience a lot of problem behavior that carries over into our next activity. However, because of this teacher’s tight transition, it’s like she created time that didn’t exist before!

So how do they do this?

Just good kids? Offer them a pizza party to pretend just for this video?

No, it can happen in real life with real students. If we teach them. Anything we want the students to do, we have to teach. And that, of course, doesn’t mean just telling them. We model the routine, engage in guided practice, and give opportunities for independent and natural practice, all with feedback along the way. And we reteach at different times throughout the school year to ensure students maintain these skills.

One last note on routines: some might see the clip above and think yes, of course, this is just for elementary kids. My response is Heck No! All ages of students benefit from routines (and all of the classroom management strategies I’m addressing here). You might adjust the language and steps you use to be more appropriate for your student population. That said, I’ve seen some amazing classroom transition routines in high schools that included students with (usually) very challenging behavior following right along.

2. Post, teach, review, monitor, and reinforce expectations

The next classroom practice is to establish a small set of expectations of what you want students to do universally, pretty much across all contexts and situations. These expectations are positively stated containers that encompass all the desired behavior you want from students.

Ideally, these are already established school-wide. A common example you’ll find in a lot of schools is Be Respectful, Be Responsible, Be Safe. Think about how these tell students what you want from them all the time. It doesn’t matter if they’re in small groups, walking the hallway, eating lunch, going to the bathroom, whatever—the expectation is always to be respectful, responsible, and safe. Even if your school doesn’t have these (or they’re dead in practice, just written on faded, ignored posters on a wall somewhere), you can establish your own.

Within these expectations, you can establish a small set of rules, which are clear definitions of what it looks like to follow expectations during specific activities, routines, or situations. For example you might describe what you want from students to be responsible during certain instructional routines, like whole-group instruction, small group work, independent work, etc.

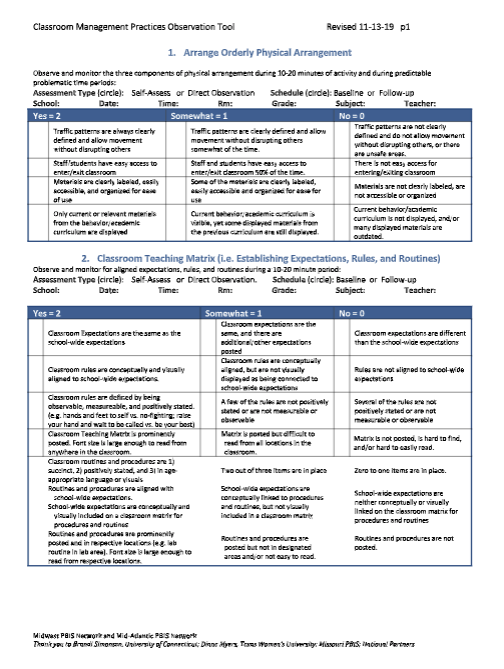

A great way to do this is with a classroom teaching matrix, like this:

Classroom Teaching Matrix from Creating a Classroom Teaching Matrix Brief – Center on PBIS

Figuring these expectations and rules out is just part of the journey. Just like with routines, these need to be taught and reviewed throughout the year. And as part of your active supervision, you can be looking for students who are actually following your expectations and acknowledge their good work to reinforce what you want in your classroom.

But shouldn’t they know all this already? Or shouldn’t someone else have taught them how to behave?? (hint, hint: their parents?!) Well, yes, no, maybe so…

What I try to emphasize is if students haven’t been effectively taught appropriate school behavior, then who’s going to do it? I can wish all I want that someone else would step up, but as a professional, I know it’s going to come down to me in a lot of cases. And this is totally in our wheelhouse—as teachers, we’re well-equipped to teach behavior.

My last thought on that is that even if it’s older students who’ve been around for a long time, they’ve never been your student before. They don’t know how to be your student. And I bet you do things differently than some of your colleagues. Perhaps there’s a teacher down the hall who seems all loosey-goosey with students, and that kind of controlled chaos drives you nuts. You’d never do things that way—your classroom is a place of order and peace.

Or maybe you’re the free spirit, and you’d never want to teach like a drill sergeant. Well, how do students know the difference? Especially when they have many different teachers.

It all comes down to what we teach them.

All students do better when they know exactly what we expect of them, and especially students who tend to struggle with challenging behavior.

3. Actively engage students in instruction

Now we’re into the classroom management strategy that might speak to your heart—good instruction. It turns out students behave better when involved in great teaching.

And that’s the key—they have to be involved. Actively engaged in instruction. Not just passive recipients.

This is some crazy rocket science, I know, but it turns out the more time students spend actively engaged in their learning, the more they learn! Shocking, I know!

“The relationship between engaged time and student achievement has the same scientific status as the concept of homeostasis in biology, reinforcement in psychology, or gravity in physics.”

Researcher David Berliner

A simple idea, obviously, but so very important to our work. When actively engaged, not only do students learn more, they behave better. It’s more difficult for engaged students to be disruptive or distracted or to seek out *fun* diversions from instruction.

So it’s important to maximize instructional activities that actively involve students.

One simple practice is to include strategies that increase opportunities to respond for all students during instruction. Opportunities to respond are any method a teacher uses where students must do something, such as asking a question or choral responding (like in the transition video above) or other strategies like think-pair-share.

A traditional instructional strategy has been for teachers to ask a question and have one or two students give an answer. If you used a heat map of the seating chart to see who participated, I bet you wouldn’t be surprised to find it’s the same few students who answer most of the questions. Then, there’s a few more who occasionally answer. And there are some that never answer anything. Students know they can disengage (and do) with this approach.

Researchers have done a ton of studies around teachers increasing opportunities to respond for all students, including students with very challenging behavior, finding that students become more actively engaged, behave better, and learn more. Who wouldn’t want that??

4. Implement a continuum of responses to acknowledge appropriate behavior

Next, it’s important to think about what the heck we’re gonna do when students actually do what we want them to. When they exhibit the kind of behavior we want. The things we taught them.

When we respond in positive ways to desired behaviors, it has a powerful impact on student behavior and the climate in our classroom. And we’re more likely to see more of those behaviors in the future.

So one of the most important classroom management strategies we can employ is to acknowledge and reinforce the appropriate behavior we want to see in our classrooms.

Here we can think of a continuum or spectrum of planned responses to appropriate behavior.

On the most practical end of the spectrum, we can simply positively acknowledge desired behavior when we see it. The best way to do this is through behavior-specific praise, which is basically just telling a student what they did well (e.g., “great job raising your hand first”).

You might choose to implement more intensive evidence-based reinforcers to support appropriate behavior. In the middle of the spectrum, this might be something like occasional group contingencies (i.e., students in the class earn a reward if one or more of them meet certain behavior expectations, depending on how you set it up) or individual contingencies with specific students who need a bit more support (e.g., a behavior contract).

Token economies can take more effort to set up and run but offer a powerful way to promote better student behavior. I’ve seen a lot of teachers implement some version of scholar dollars where students earn classroom money that can be exchanged occasionally for certain privileges or rewards.

Note that these reinforcers don’t have to be tangible items like candy if that isn’t your thing (or you wallet’s thing!). You can go a long way with just the power of your words through positive feedback or with certain privileges (e.g., a homework pass, break pass, time for a preferred activity, seating choice).

5. Implement a continuum of responses to inappropriate behavior

Last—and I think last for a reason— is to think about what the heck we’re gonna do when students don’t do what we want them to.

This is where teachers sometimes try to start when thinking about classroom management: what do we do when kids misbehave? (And really, we often mean: what punishments will work?)

But the classroom management strategies we’ve discussed so far are about setting up students for success in the first place, and assuming that they can, in fact, be successful with the right support.

That said, there’s no behavior strategy that’s a miracle cure.

Students are still going to engage in inappropriate behavior at time, even if we implement the first four strategies very well. It’ll be less often than without those strategies, but still a reality. Just like academics—even with our best instruction, students still make errors. And some more than others.

It’s helpful to think of misbehavior as errors that require intervention and more instruction. Great teachers have an array of possible responses when students are struggling to master academic content. And it’s just the same for behavior.

So just like the previous classroom practice, here we want to plan a continuum of possible responses to inappropriate behaviors ranging from simple to more intensive.

On the simple, practical end, we can still rely on the power of our words through feedback. Corrective feedback, in particular, which is when we give brief, specific, corrective information to a student about what we want them to do instead.

This feedback isn’t just a reprimand (e.g., “No!”, “Stop that!”). What’s important is that we tell the student explicitly what we want to see them do. They’re more likely to do it! (Imagine if we just said “No!” or “Stop that!” and moved on when students made academic errors without any instruction or guidance).

A more moderate effort response might be to spend some time individually re-teaching expectations to the student, especially if we’re seeing a pattern of the same problem behavior.

There are other strategies we can plan that can be powerful agents of change when implemented appropriately such as planned ignoring (when a student is misbehaving to get teacher attention) or time out from positive reinforcement (which is a brief, structured removal of a student from a reinforcing activity/setting).

And we may need to have some practical interventions in our toolbox to improve the likelihood of certain students’ success. I share about those on this site, such as precision requests, choice, and behavior momentum. Keep in mind, though, that successful behavior interventions rely on having a strong classroom management foundation.

Why is Classroom Management Important?

If it isn’t already clear enough from what you’ve read so far, effective classroom management is essential.

Teachers who proactively plan and implement classroom management strategies benefit from students who spend more time engaged in learning (so they learn more!) and less time messing things up for themselves, their peers, and, well, you.

Simply put, students don’t necessarily know better and benefit from explicit instruction and support to know how to be your student.

Classroom management isn’t a silver bullet for all behavior woes, but it serves as a foundation that lowers the probability of misbehavior for all students and increases the likelihood that your behavior interventions will actually work for the students who need them.

What Behavior Problems Can Classroom Management Strategies Help with?

Classroom management is related to virtually all problem behaviors a teacher might encounter. And certainly the most common, frequent challenges teacher’s face like disruption, disrespect, and disengagement (and nowadays, I guess issues with devices!). can improve a variety of behaviors. It’s especially helpful for improving compliance by increasing the probability students will follow directions. Choice can also increase a student’s motivation and level of engagement on tasks as well as assignment completion.

Besides just a reduction of the probability of behavior problems, a well-managed classroom is more productive. Students are better able to focus their energies on learning activities, and their teachers are too. This leads to greater learning.

Are these Classroom Management Strategies Evidence-Based Practices?

Lemonade

In brief, classroom management is a broad set of strategies teachers may employ to improve student behavior, rather than a distinct strategy.

In this article, a team of researchers systematically reviewed the existing evidence base to identify specific strategies related to classroom management that met their criteria to be considered evidence-based.

Their team identified 20 evidence-based practices that fit within five overall essential features of evidence-based classroom management (the five classroom practices I’ve described in this article). Specifically, they identified the following features and sub-practices:

High classroom structure (e.g., amount of teacher directed activity)

Physical arrangement that minimizes distraction and crowding

Post, teach, review, and provide feedback on expectations

Active supervision

Rate of opportunities to respond

Response cards

Direct instruction

Computer-assisted instruction

Classwide peer tutoring

Guided notes

Specific and/or contingent praise

Classwide group contingencies

Behavioral contracting

Token economies

Error corrections

Performance feedback (with and without the addition of other evidence-based strategies)

Differential reinforcement

Planned ignoring plus contingent praise and/or instruction of classroom rules

Response cost

Time out from reinforcement

Classroom Management Strategies Guides, Examples, & Resources

The IRIS Center out of Vanderbilt wonderful free training modules on classroom management essentials and developing classroom management plans (as well as a wide variety of other topics).

Midwest PBIS has great, brief snapshots that give an overview of each classroom practice as well as an observation rubric to help assess (or self-assess) whether each is fully in place.

Video Examples of Classroom Management Strategies

Jefferson County Public Schools

Classroom Management Modules

I love these classroom management modules from Louisville, Kentucky. For each classroom management feature, there is a primary and a secondary video with multiple examples of the practice in action as well as teacher focus groups. Note you can click on the heading for each practice to get more resources, such as practice briefs (snapshots), overviews, and discussion guides.

Engagement Using Opportunities to Respond

Primary

Secondary

Effective Instructional Feedback

Primary

Secondary

Building Positive Relationships With Students

Primary

Secondary

Teaching School and Classroom Expectations

Primary

Secondary

Creating a Positive Learning Environment

Primary

Secondary

Effective Instruction for Behavior

Primary

Secondary

Using Prompts and Reminders

Primary

Secondary

Classroom Management Strategies

Primary

Secondary

Escalating Behaviors

Primary

Secondary

Effective Responses to Common Misbehavior

Primary

Secondary

Classroom Management Tips

- Before the school year starts, make a classroom management plan to map out how you will implement these five practices.

- It can help to go visit some colleagues who feel comfortable with classroom management, so you can see some models.

- If you have a lot of your students frequently engaging in minor misbehavior, behavior intervention strategies may not be the best starting place. It may be helpful to evaluate and improve (if possible) the classroom management practices you have in place. You might have a trusted peer come observe you or complete your own self-assessment (example classroom management assessment) to help determine next steps.

- If it feels like your students are suddenly acting like they’ve never heard of your expectations or routines in the middle of the school year, it might be a great time to reteach them. Better yet, you might proactively plan now for certain times of the year to reteach these (e.g., when coming back from a break).

- If you haven’t ever received any classroom management training (which is common), it may be helpful to pursue it, such as trying out one of the free training modules in the resources above.